By Seeraj Mohamed | Amandla Issue 61/62 | 18 January 2019

The MEC, financialisation and the crisis

The solutions we develop to solve a crisis depends on how we understand the crisis. This understanding will be influenced by ideology and material interests. My analysis of the South African economy takes into account the role of big business, the state and the worker and community struggles that shaped the historical evolution of the economy. This analysis would be incomplete without also studying the role of changing global forces and their influence on outcomes over time. In short, I share the view of Fine and Rustomjee, in their 1996 book The Political Economy of South Africa: From Minerals Energy Complex to Industrialisation that the South African economy has been dominated by a system of accumulation they refer to as the Minerals and Energy Complex (MEC).

The MEC does not refer only to the sectors that dominate the productive part of the economy. It also includes consideration of its relation to other economic sectors such as finance, the state and class dynamics. Over time, the South African economy has become financialised, but the increasing role and dominance of finance in the economy has not diminished the role of the MEC. In fact, the MEC sectors have become increasingly dominated by finance and short-term financial motives.

Financialisation of an economy with an MEC at its core has made the economy more reliant on the capital- and energy-intensive MEC sectors. The consequence has been continued high and growing levels of unemployment in the economy and a trend towards casualisation, outsourcing and informalisation that makes employment more precarious and has weakened organised labour. The environmental and social consequences of this dependence on MEC sectors is that these sectors profit from damaging the environment and using up non-renewable resources, while the negative effects are unequally borne by the poorest parts of the population.

Finance and the large financialised non-financial corporations have benefited from the rents associated with mining and minerals and their dominant market positions in the domestic economy and the increasing precariousness of jobs. They have also become increasingly internationalised and detached from the productive economy in South Africa. As a result, the market capitalisation of the large corporations grows, while fixed investment and employment, particularly in productive sectors, decline and deindustrialisation proceeds at a scary pace.

Unfortunately, the view that the growth of the services sectors will drive economic growth and increase employment still has currency with government and big business. This notion was shown to be seriously flawed by the large negative impact of the global financial crisis on the South African economy that suffered huge job losses and economic recession. There was growth in investment, employment and economic growth in South Africa in the few years before the global financial crisis. But this was the result of debt-driven consumption and speculation in financial and real estate markets. This growth collapsed when credit markets in South Africa and globally dried up with the global financial crisis.

I have argued over the past decade that the South African economy was on an unsustainable path and would have had its own meltdown and crisis even if there had not been a global financial crisis. South Africa’s economic growth projections have been continuously revised downward over the past few years by the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, private banks and South Africa’s National Treasury and Reserve Bank. This indicates that these institutions and their models have failed to recognise that growth based on debt-driven consumption and speculation in financial and real estate markets was not sustainable.

Neoliberal economic policies, including inflation targeting and fiscal consolidation, exacerbated the poor performance of the economy during the post-crisis period. The economic performance of the economy was poor but the financial markets were booming and large quantities of money left the economy legally and illegally. The economy remains on an unsustainable path and economic growth, investment and employment has stagnated. Unfortunately, the government still seems to believe that showing commitment to neoliberal economic policies and pandering to credit ratings agencies will increase business confidence and so magically fix the economy.

South Africa’s political economy crisis

The political crisis of South Africa is that after more than two decades the economy does not come even close to adequately serving all the people of the country. South Africa remains a country characterised by extraordinarily high levels of inequality, poverty and unemployment. Until the transition to democracy during the early 1990s, high levels of poverty, inequality and unemployment would have been expected because of the long and deep legacy of colonialism and apartheid.

Much of the character of South African capitalism and its institutions is still shaped by systematic racism. Much of the crisis today is related to the continuing legacy of colonialism and apartheid. The post-apartheid state has been unable and often unwilling to address the problem that most wealth and economic power remains concentrated with a small minority of the population.

There have been positive changes due to democracy, such as increasing welfare provisions, electrification, housing etc. However, economic and other policy choices of the post-apartheid government have contributed to and often exacerbated the legacy of poverty and inequality. These choices have allowed financialisation of the economy and even greater concentration of economic wealth and power. At the same time, these choices allowed international financiers and ratings agencies increasing influence and power to approve the proposed economic policies and actions of the state. State capture and the scramble to join the economic elite by many of those with political influence is but one symptom of these negative economic developments.

In allowing a neoliberal ideology to dominate its economic thinking government has willfully moved away from the vision of the South African state becoming a developmental state. The financialisation of large corporations has increased the influence of the shareholder value movement over how these corporations are run. It has caused them to fixate on increasing short-term returns and share prices. In a sense, big business and the state in South Africa have left the planning of the future direction of the South African economy to institutional investors and the shareholder value movement, whose short-term concerns for high returns destroys rather than creates value in corporations and economies.

Looking ahead

Some economists use the term “path dependency” to refer to the forces shaping economic outcomes in a country. The analogy seems to be that there is a rut in the road that guides the wheels of a vehicle. In South Africa’s case, the absence of a developmental state to influence economic growth means that it will be all but impossible to steer the economy out of the current rut. First steps in the correct direction would entail somehow instituting a developmental state that reverses financialisation of the economy through regulating domestic financial institutions and international financial relations. That developmental state would have to play an active role in the allocation of capital away from speculative activities in financial and real estate markets and towards investment in productive sectors.

Several strands of the economic development literature stress the importance of manufacturing as an engine of growth. At a global level, the deepening, diversification and growth of manufacturing has allowed countries to break out of the problems of dependence on production and export of primary goods, particularly mining and minerals. A developmental strategy that supports the growth of manufacturing has the ability to reshape the economy because it creates an economy with a different type of services base. This supports further beneficiation of domestically produced primary goods and the marketing, retailing, distribution and export of these manufactured products.

Further, domestic production of manufactured goods would support the development of a larger, stable and better skilled industrial working class. Industrial workers and workers in associated dynamic services businesses would be able to organise in the workplace and communities to assert more power to deepen democratic practices in the workplace, the economy and the country as a whole.

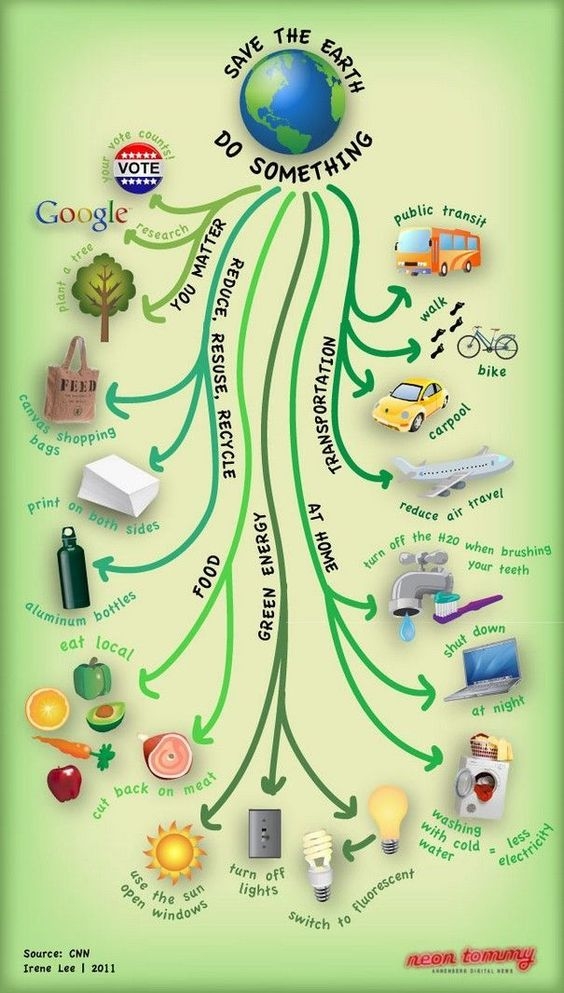

A strategy that focuses on improving the lives of the poor through providing needed goods and services and greening the industries and firms that provide these could help move the South African economy out of the rut. The growth of manufacturing could lead to a more dynamic and productive services sector and services jobs. South Africa has a services sector dominated by finance, retailing, outsourcing and private security that reflects the dominance of the MEC and the financialisation of the economy. It grew on the backs of increasing levels of inequality and poverty within the economy. Growth in manufacturing and green jobs would reshape the services economy to better serve all South Africans.

Seeraj Mohamed is an economist with a focus on macroeconomics, finance and development. This article is written in his personal capacity and does not reflect the views of his employer or organisations he is affiliated wit