Opinion & Analysis / 27 November 2018, 3:53pm / EBRAHIM HARVEY

I

cannot believe Mineral Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe is the same

man I first met when we were both in trade unions in the 1980s.

He was then a militant and powerful National Union of Mineworkers

(NUM) shop steward in Welkom. Today the man is hardly recognisable.

But this is what often happens when people ascend to positions of

authority. There can be no doubt that obtaining such power – in this

case going from a miner to a cabinet minister – has changed him.

There is ample global and historical evidence of what happens when

people ascend to such positions. They are softened or compromised by the

material, financial and other seducements that go with power.

Last week Mantashe bemoaned the Pretoria High Court ruling in the heated Xolobeni mining dispute. The court ruled in favour of the Amadiba Crisis Committee which objected to his ministry granting a licence to an Australian mining company, Transworld Energy and Mineral Resources, without the consent of the community.

In a precedent-setting case, Judge Annali Basson ruled that the company and the Department of Mineral Resources could not run roughshod over the concerns the Xolobeni community has with mining in the area, and that it could not proceed unless it had the consent of the community.

This is not the only case in which communities are up in arms over

mining operations; similar struggles are going on elsewhere.

The

thing that unpleasantly surprised me is that, as the former leader of

the NUM, Mantashe knows of the atrocious record of mining companies and

the burdens they inflicted on miners and their communities.

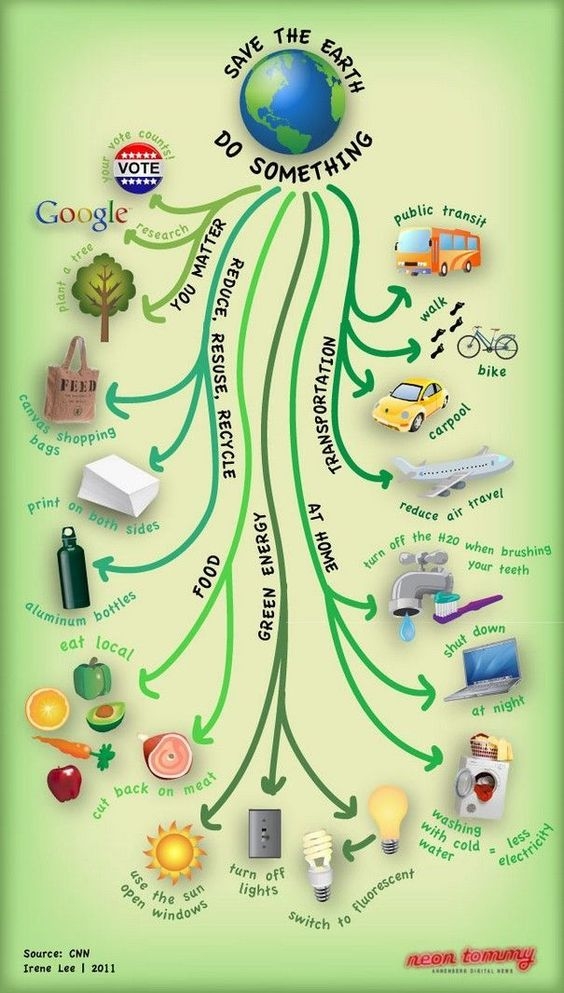

Miners, especially migrant workers, their families and communities

have been exploited and abused for decades. This is besides the harmful

consequences mining has on the immediate environment and health of

nearby communities.

The main gripe Mantashe has with the judgment is that it will mean

his ministry will no longer have an untrammelled right to grant licences

without the consent of affected communities. Is that not what he would

have insisted on if he was still the NUM leader?

What should be seen as a huge victory for working-class mining communities, he sees as a bad judgment.

Mantashe is opposed to affected communities having the power to stop

mining which they are not happy with. He is basically saying the

granting of licences is a government decision, which those communities

don’t have a right to interfere with.

But how can a former mineworkers’ leader argue like that, and thereby disregard and disrespect the feelings of the community?

Instead he wants the community to yield to the power of the government and mining companies.

Mantashe forgets that the Xolobeni community’s opposition is born

out of the experiences black miners and their communities have had with

the mining companies whose interests were often overwhelmingly

exploitative.

In fact he has not only forgotten his roots, he is acting against

the interests of the community which arise. It is no exaggeration to

state that local and foreign mining companies have devastated black

communities for too long.

What the Xolobeni community is therefore asserting is their right to

fight for their own interests, especially in a supposed post-apartheid

South Africa.

Mantashe fails to realise that the Xolobeni victory

has positive and inspiring implications for miners, their families and

related communities.

He should have joined the jubilant celebration outside the court

following Basson’s decision. Instead, he was probably inconsolably

depressed in his office in Parliament. But this is a manifestation of

the vicissitudes of struggle and politics.

It is sad to see Mantashe support the licensing of the company, but chastise the court decision favouring the community.

That sums up the growing distance between the ruling ANC and its mass support base for more than a decade.

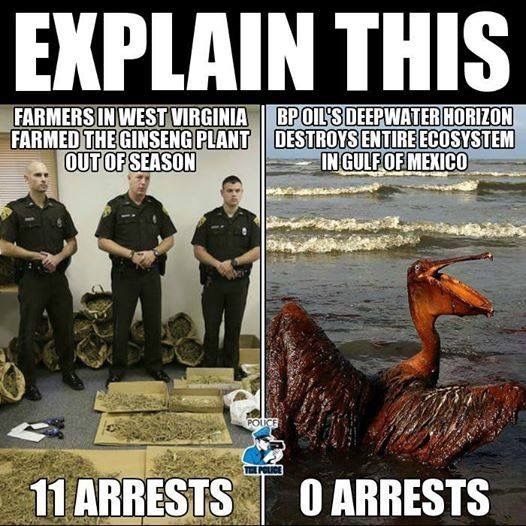

Richard Spoor, the lawyer representing Xolobeni residents, was assaulted by police, arrested and charged.

The ANC’s jackboot has countless times been seen in clashes between

community protesters and the police. This is the ugly face of the

post-apartheid ANC that black people never thought they would see before

1994.

Besides, research will show mining communities have benefited little from the royalties the mining companies pay the state.

Increasingly, Mantashe looks more like a company representative than a former leader of mineworkers.